How I would grow Substack

Substack has two futures. The first is one where it sticks to its current model, eventually hits a wall in growth, and is replaced by substitute products in a race to the bottom. The second is one where it evolves beyond its current form and becomes the internet's most dominant and content-creator friendly writing platform. [^1]

This might seem a bit doom and gloom. Substack is a great product; it's attracting some serious writing talent and is backed by the likes of Andreessen Horowitz and YCombinator. But Substack is in a growth phase where their challenges will soon be qualitatively different from when they were still looking for product market fit.

In this post I'll walk through what I think Substack should do, and why.

If you want to skip straight to the part where I make specific feature recommendations, you can go to Part III: Moving off email.

I. Email as a distribution channel

Substack was built from the ground up with email distribution in mind (and as a result is a good example of product channel fit). Email is a unique distribution channel because inboxes are highly personal. Inboxes exist in silos; when you invite people into your inbox, their emails live in a vacuum from the rest of the world.

Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie has written about his vision for Substack's future as an intertwined network of publications:

Today, Substack publications are like islands on their own, with little communication between each. But over time, we aim to build Substack into a network, where writers can support each other and readers can find millions of deeply satisfying media experiences. As the network grows, there’ll be opportunity for cooperation, community, and innovation.

My thesis is that getting readers out of their inbox and onto the Substack platform will result in more growth and be a necessary step in turning Substack into a "network" rather than a series of separate islands.

Why is this important? Stronger network → stronger network effects, and stronger network effects → growth.

Network effects

A business with strong network effects creates more value for each user for every additional user it adds. This kind of business gets more powerful with scale and has huge, accelerating growth potential.

Substack has weak network effects. Let's look at them from the perspective of its two types of users: readers and writers.

Readers

Readers don't demand Substack. They consume newsletter content in their inboxes and care approximately 0% about the platform that was used to distribute those newsletters. They also don't care if the newsletter they're reading has an audience of 50 or 50,000 — for all intents and purposes, they're completely unaware of the existence of other readers.

Writers

Writers love Substack because it makes setting up newsletters and collecting payments on them easy. Substack's model is built so that their writers aren't building equity in Substack — they're building equity in their email list. The communities they are building are mostly represented by the email addresses they have, which are completely independent of the Substack platform itself.

This is both good and bad. It's good, because writers like being in control of their audiences. But it's bad, because this means that there are low switching costs in moving to whatever the latest writing platform flavor of the day is. [^2]

The right way to solve this problem isn’t to take away value from writers by reducing their control over their audience, but to add value for readers so that they demand Substack rather than being platform-agnostic in their inboxes.

One way to achieve this is by helping writers build communities around their publications that live on their personal Substack pages. Substack publications tend to be built around long-tail audiences who are likely to find a community of like-minded people valuable, so all Substack needs to do is provide tools to help writers in their community building.

There are already signs that Substack is moving in this direction. Last year they launched a "community" feature where writers could create discussion threads for readers. Doubling down on communities is a good bet for Substack if they're concerned about network effects.

But how?

II. Building communities

I've heard people describe Substack as the next Medium. I think it would be a mistake for Substack to model itself in this way — it would be much more ambitious for Substack to try and be the next Twitch. [^3]

Twitch has two categories of users: streamers, who are analogous to writers on Substack, and viewers, who are like readers. Streamers host livestreams of themselves playing and talking about (usually) video games. Viewers interact with the stream through a chatroom that takes up the right-hand side of the interface.

Like Substack, Twitch streamers are relatively niche. They support a small audience compared to Youtube, which is the closest meaningful alternative for gaming content creators. But Twitch audiences are highly valuable long-tail users who are much more likely to be active, obsessive fans of the content creator than passive consumers.

The top Twitch streamers generate incomes of $10M+ per year. Streamers make money in a few different ways, but let's go through the two main ones.

Subscriptions

Viewers can pay either $5p/m, $10p/m or $25p/m to subscribe to a streamer. You might assume that Twitch has a Substack-like model where certain channels, or at least certain streams are behind a paywall that can only be accessed by subscribers. This is incorrect. If you’re a subscriber, you’re identical to a regular viewer in every way except for three, maybe four crucial areas.

First, when you participate in the stream’s chat, you get a special badge next to your username that shows everybody that you’re a subscriber to the stream. You can also get special badges for being a long-time subscriber.

Second, you get access to “emotes”, which are emojis that you can use in Twitch chat. Each streamer gives subscribers access to their own special, unique emotes, and they’re often associated with some kind of inside joke within that community. Moreover, not only do you get access to emotes, streamers can unlock more custom emotes for their subscribers based on the number of subscribers they have. This means that subscribing to a stream isn't just an altruistic act for the streamer, but a favor to the entire community.

Third, depending on your streamer’s settings your name may briefly appear on the stream and the streamer may or may not give you a five-second shout-out.

Fourth, you don't get any ads. I don't think this is a particularly great incentive for most viewers since ad-blockers are so common within the Twitch viewer demographic.

Donations

If you think that it’s a stretch to ask gamers to spend $5 a month for the privilege of “subscribing” to a content creator they had access to for free anyway, you’d be even more surprised to know that they also love freely donating money to them.

You can donate directly by using credit card/Paypal or by purchasing "bits", which are Twitch's virtual currency. Bits can be redeemed for "cheers", which are emotes you can use in a stream. You can also indirectly donate to streamers by donating subscriptions to their stream to other viewers.

If you donate to a streamer, your name may briefly appear on the stream and the streamer may or may not give you a five-second shout-out. If you’re particularly generous, your name might also appear on a leaderboard of top donors.

What Twitch has managed to achieve is seriously impressive. How have they managed to get viewers, many of whom have barely any disposable income, to pay for emojis? There are two explanations:

Altruistic motive. Viewers give money to streamers because they want to support the stream. They want to support the stream because they (a) find value in the content they consume and (b) feel a personal connection to the streamer.

Selfish motive. Viewers want to (a) gain access to the streamer, (b) gain access to the streamer's community, and (c) buy increased status within that community. Spamming inside-joke emojis in chat with the subscriber icon flashing by your username is a great way to signal to everyone that “hey I’m part of your tribe too!”. Having the streamer personally thank you when you make a donation also buys a short but direct, personal interaction with the leader of the community in front of the entire stream.

Let’s compare the incentives behind supporting a writer on Substack and a streamer on Twitch. Substack is doing a pretty good job with (1), but Substack publications lack a sense of community that would foster closer personal connections between writers and readers.

The same applies to (2). Yes, the fact that you can only access certain newsletters and posts by becoming a paid subscriber is a big plus for the selfish motive. But becoming a newsletter subscriber doesn't give you special access to its community, or to status within that community.

III. Moving off email

So far, this post has been a roundabout way of me saying that Substack should think about prioritizing the creation of communities around its content creators' personal Substack pages. I've made a case that this will help growth because (1) it will strengthen network effects, and (2) it will create opportunities to increase ARPU.

Step 1 towards building communities is shifting Substack's center of gravity away from the readers' inboxes and into the newsletters' Substack pages. This will help writers form the networks of "cooperation, community, and innovation" that Hamish refers to.

There are two very simple experiments Substack could run right away to get their feet wet with moving away from email:

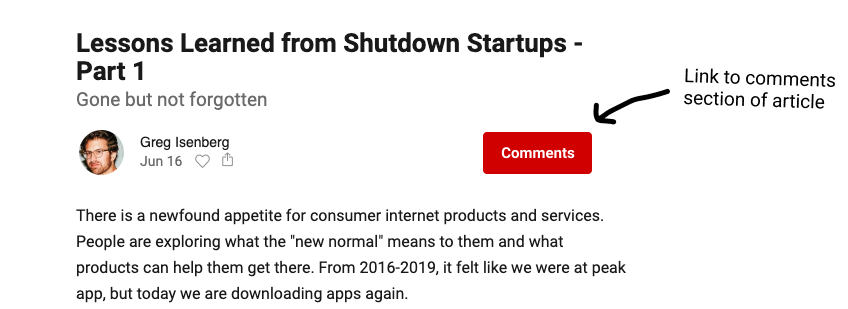

a button to see comments at the top of each email; and

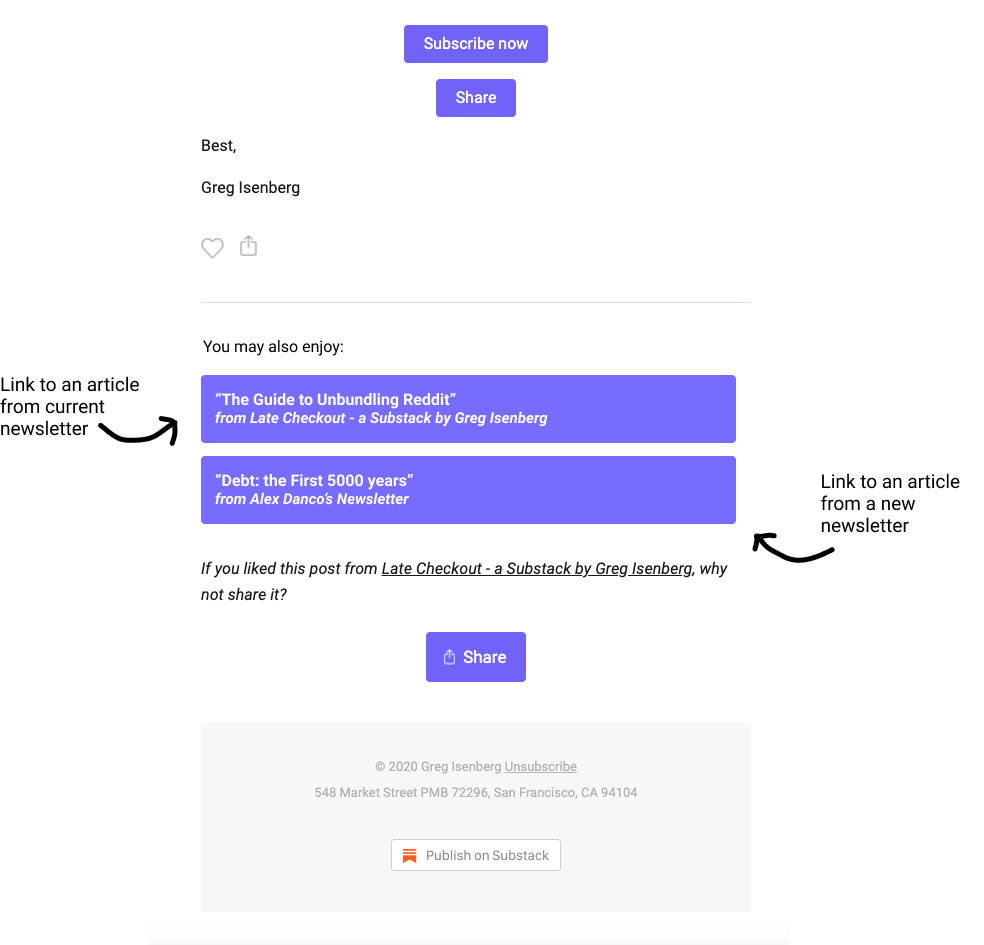

displaying "related posts and newsletters" at the bottom of each email.

Comments button

Substack could add a "comments" button at the top of each newsletter to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: adding a "comments" button at the top of each newsletter would increase the average number of comments per article.

Hypothesis 2: users will want to read the comments of an article in their inbox.

Hypothesis 1 seems pretty self-evident and easily testable. But it's useful to test the extent to which a comments button would increase engagement (in the form of leaving comments) because these data will help us answer hypothesis 2.

I think this is directionally the right area to explore, because when I'm done reading a great post, the first thing I want to know is what other people have to say about it. I don't think I'm alone. We're memetic creatures. There's a phenomenon on link aggregating websites like Reddit and HackerNews where users will read a headline and then go straight to the comments section of an article without bothering to read the article itself.

Comments are also inherently social, so encouraging them would be a step towards building communities on Substack.

This feature does two things:

(a) helps writers build communities around their newsletters; and

(b) funnels users from their inboxes into their Newsletter's profile.

(a) and (b) build network effects because they mean that as Substack grows, readers and writers will find the platform increasingly valuable.

If this experiment is successful, Substack could consider making "average comments per article" (let's call this ACPA) a North Star Metric in order to explicitly optimize for comments across the entire company. ACPA could be a good proxy measurement of Substack's success in moving readers onto its platform and a leading indicator of reader engagement + community building.

Overall I'd like to see Substack treat comments and discussion threads as a first-class citizen within its platform. It's true that the average news article comments section is very low value. If anything, comment sections are usually a net-negative to the overall user experience. But if Substack brought comments forward onto the center stage, discussions could resemble the message boards and IRC channels of Web 1.0 — think Discord channels rather than Facebook comment sections on news stories.

Related posts and newsletters

This feature is a section at the bottom of each article that recommends two new posts for the reader to look at: another post from the same newsletter, and a post from another newsletter.

The primary purpose of this feature is that it gets users out of the inbox, and onto the Substack platform itself. It also helps users discover new content — and in particular, new newsletters — that are likely to appeal to them.

We can test these hypotheses with this feature:

Hypothesis 1: adding a "related posts" feature will increase reader engagement measured in # of newsletters read.

Hypothesis 2: adding a "related newsletter" feature will increase the average number of subscriptions per reader.

Substack doesn't focus much on content discovery. A cursory look at their landing page suggests that this is mostly intentional. Substack writers build their income through niche audiences, so content discovery would need to be handled differently than to, say, Medium, where writers are generally targeting a much broader cross-section of society. Ideally, though, writers would be able to use Substack to meaningfully expand their existing audiences through the platform itself.

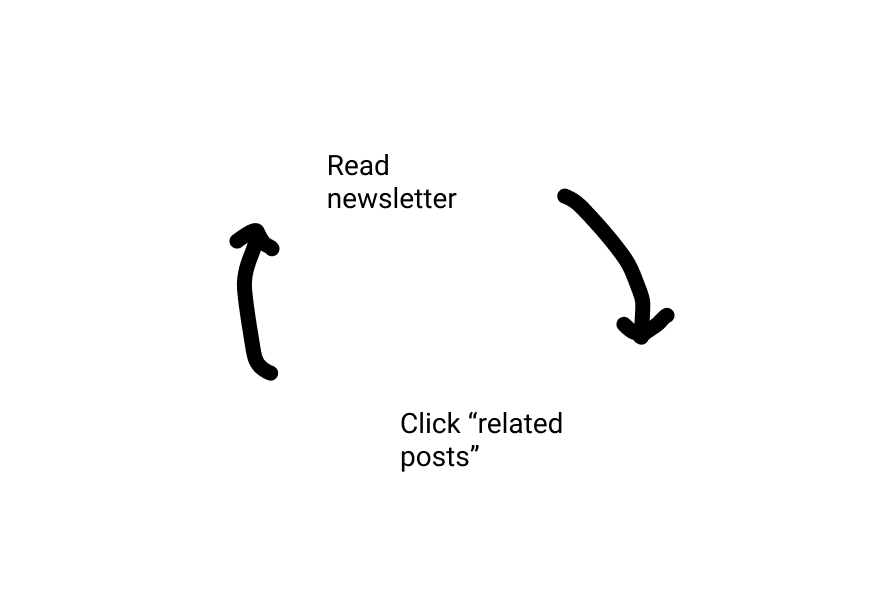

This feature would help with content discovery, because, in theory, it's a loop. The more content users consume, the more new content they will discover. If the average Substack user is anything like me, they are susceptible to falling down rabbit holes of interesting writing. Our hypotheses will test whether this feature is enough to nudge users down that hole.

The value proposition for this feature looks like this:

it's good for readers, because readers derive value from Substack by reading posts they like, and this feature helps users access that value more frequently; and

it's good for writers, because their readers will be more engaged with their content, and because it makes their content more discoverable to outsiders.

The average number of newsletters subscribed to per subscriber metric could be an effective leading indicator for annual revenue per user — the more newsletters a reader is subscribed to at the top of the funnel, the more opportunities there are to monetize that reader further down the road.

IV. Hidden costs

Substack CEO Chris Best has said that "[t]he things that help growth can hurt users." This is partially because the trade-offs that come with "growth hacks" are often less quantitatively measurable than the up-side, so they're abandoned.

Even the two minor features I've suggested come at a cost. They reduce the control writers have over the presentation of their newsletters and create visual pollution in readers' emails. You could try and measure these costs indirectly through metrics like NPS, but ultimately it's much less quantifiable than something like "average comments per article". It's part of the reason why these ideas might not seem particularly ambitious — they're deliberately intended to be small, iterative steps towards the path that I think Substack should be heading down.

But although these features are small, they're important, because they would represent a broader intent from Substack to move away from inboxes and towards community building. This is how Substack wins.

[1] It doesn’t have to stop at writing. Substack has been experimenting with podcasting, and everything I say in this post about the writer/reader relationship also applies to podcasts.

[2] This is probably why Substack can only afford to take a 10% cut of subscription revenue. In comparison, Twitch takes between 30-50%.

[3] Incidentally, Twitch CEO Emmet Shear is an early investor in Substack, which makes me wonder if he sees similar parallels between Substack and Twitch.